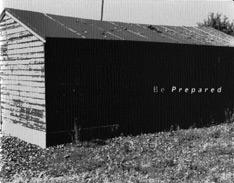

Be prepared

John Duncan’s photographs disappoint. They do this so single-mindedly it’s disturbing. This is indeed Belfast but I don’t see it. These are public spaces yet they lie deserted. For the most part they are taken under open skies yet there’s never a genuine horizon. Objects are positioned there but they are never “whole”. They seem well used but it’s not clear why. There are hints of past events yet nothing points to their true function.

The criminologist is helpless: please, photograph, tell me what happened; tell me whom this hut belongs to; why these walls have crumbled, never been rebuilt, and yet one still stands, colours still bright; who sat on this chair; what is this wall doing here; why is this brick hanging from the sky; who or what did someone expect to meet with this pointed end of a wooden stake now lying on the road; who dropped this crank at the road’s edge, who stumbled across it, who was struck down with it; does this dark brown surface in front of me belong to a wall or a postbox, and what’s going on with this wooden block; where is the dog; and the chairs in the background, who threw them there? There are no answers. For it’s not about objects but pictures of objects.

The story of the approach to perspective in Duncan’s photography is the story of the search for a safe place of human existence as opposed to God’s guarantee of world order. This was a measurable, rationalised order; a reliably representational portrayal and recording of the connection between objects and the assurance of perspective as a means of positive vision. In “be prepared” all this appears to be absent. This is not new, here the absence is presented in strangly ominous ways. Duncan doesn’t use photographic equipment in the interests of a narrative order, nor to record remnants of the authentic. He finds, instead, graphically structural metaphors for the singularity of appearances in the chaos of an unordered world. The imaginary space loses its dimension in the inefficacy and irrelation of objects. Or, alternatively: there is such a lack of understanding that one loses one’s own dimension and ability to draw connections between objects. What takes place here is a sort of extinguishing of the value of memory through the course of a particular viewing. It must have been the same for Gulliver on his travels: to look at a wooden surface and not know if it’s the seat of a chair, the floor of a dancehall or the surface of a carved button; to stand in front of a stony surface not knowing if it’s the wall of a house or the surface of a single brick; to come across a piece of sharpened wood and not have any idea if it’s a toothpick or a stake. Such an experience can bewitch. Yet Duncan denies his photographs even this. They appear sharp-edged and distanced: there is no hope of seduction, not once does colour give itself up to celebration.

Gaston Bachelard uses the symbolism of the house to contrast the public spaces of the middle floor with those of the cellar and attic. For him, the former symbolises law and order, the constitution of power. He describes a wooden filing cabinet, in a quotation to Henri Boscos, as the ideal piece of furniture for such a space: “Every time he walks past this massive piece of furniture he looks at it with satisfaction. Here at least everything remains solid and true. You see what you see, you feel what you feel. Width doesn’t penetrate height, nor emptiness fullness. Nothing here was calculated which hadn’t been foreseen by a conscientious intellect for reasons of usefulness. And what a wonderful tool! It was suited to all: it was a memory, an intelligence. Nothing can escape or float about in this well made cube. What you put in once, a hundred times, ten thousand times, can equally be found again in the twinkling of an eye so to speak. Forty-eight drawers! In there is housed an entire well ordered world of positive knowledge. Mr Carre Benoit attributes a sort of magical power to the drawer: ‘the drawer’, he once said, ‘is the basis for the human mind'”. Memory has vanished from Duncan’s images. Yet something still clings, an obstinate desire for history, all the while knowing it can no longer be gained from the objects. There is no way through this labyrinth of hints, one is thrown back on nothing but oneself and the fear felt by Kafka’s beetle. Open space has become cellar, light is nothing more than its own illusion; the criminologist stands in the dark. He’ll have to realise that this case will not be resolved so quickly.

Out of stock

Out of stock